Eugéne Leroy (1910 – 2000)

5. 9. 2013 – 27. 10. 2013

prices of paintings available upon request in the MIRO Gallery

In addition to its chosen representatives of the arts, each country with a highly developed culture has a broader base of artists who are just starting to create the right fertile ground for the arts. One of these artists was Eugène Leroy, a calm, thoughtful man who worked in a frontier town in the industrial region of northeastern France. Nowadays people no longer speak about globalization, perhaps because globalization is already a done deed. But how does the global concept affect a person closed off in their own voluntary seclusion? The opposite of global, regional, comes to mind. This word tends to be viewed by Czechs somewhat pejoratively, but it may conceal the hidden paths of artistic development – one could even say artistic endemism – with its own artistic discoveries. Location is one thing; time is a different matter. This major artist, a Frenchman who was born in 1910, should have built his career as an artist in Paris and been a part of the city’s remarkable cultural conglomerate that has earned the name of “the Paris school”. This school could have included Leroy’s art if only he had not steered clear of Paris and Paris had not avoided him. It might be an interesting, though not unique phenomenon: whereas hundreds of young artists from throughout the continent took Paris by storm, many French artists stayed home and helped create a new artistic map of France. The “exotic” regions of Brittany and Provence were discovered as early as the 19th century. Van Gogh came from rainy Holland and, his head filled with Japanese art, was fatefully attracted by the sun and colour of the south. Van Gogh and Gauguin met like two celestial bodies. Gauguin later moved to the other end of the world, fuelling travel fever among artists. One could make the argument that he and Van Gogh were also pioneers in discovering other cultures and in the later “globalization” of art (the nicest Czech example of this is the young travelling painter Otakar Nejedlý). Leroy studied at École des Beaux-Arts in Lille and Paris in the early Thirties, but he found he had to set out and learn on his own.

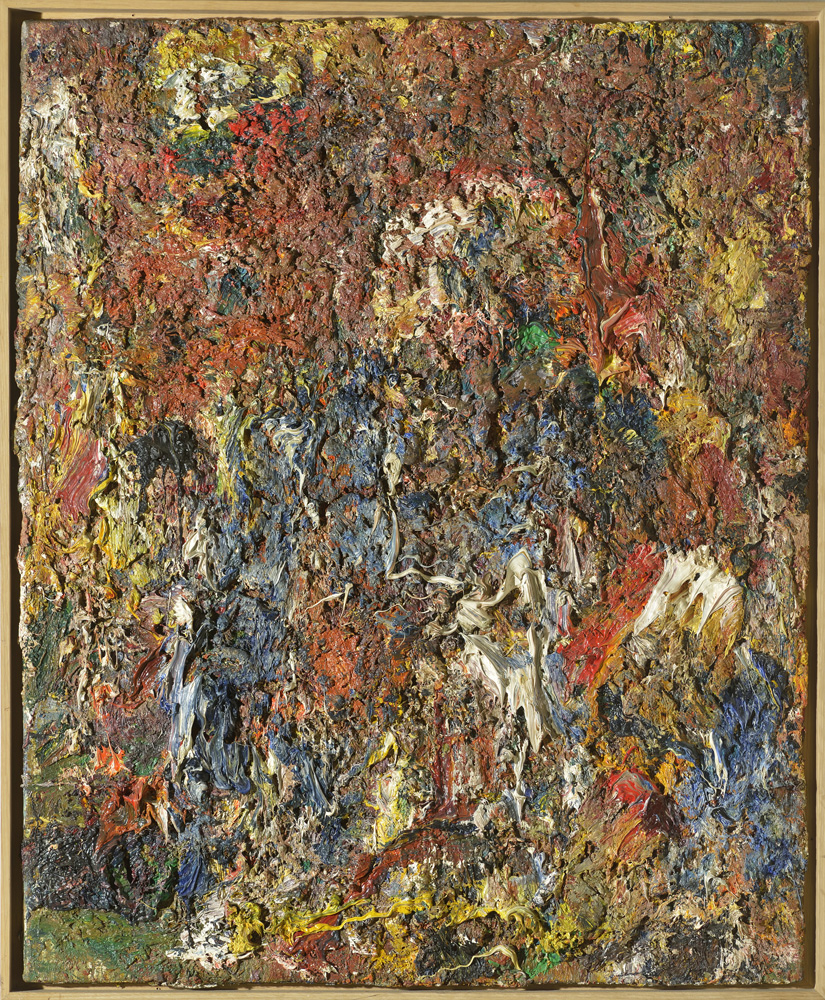

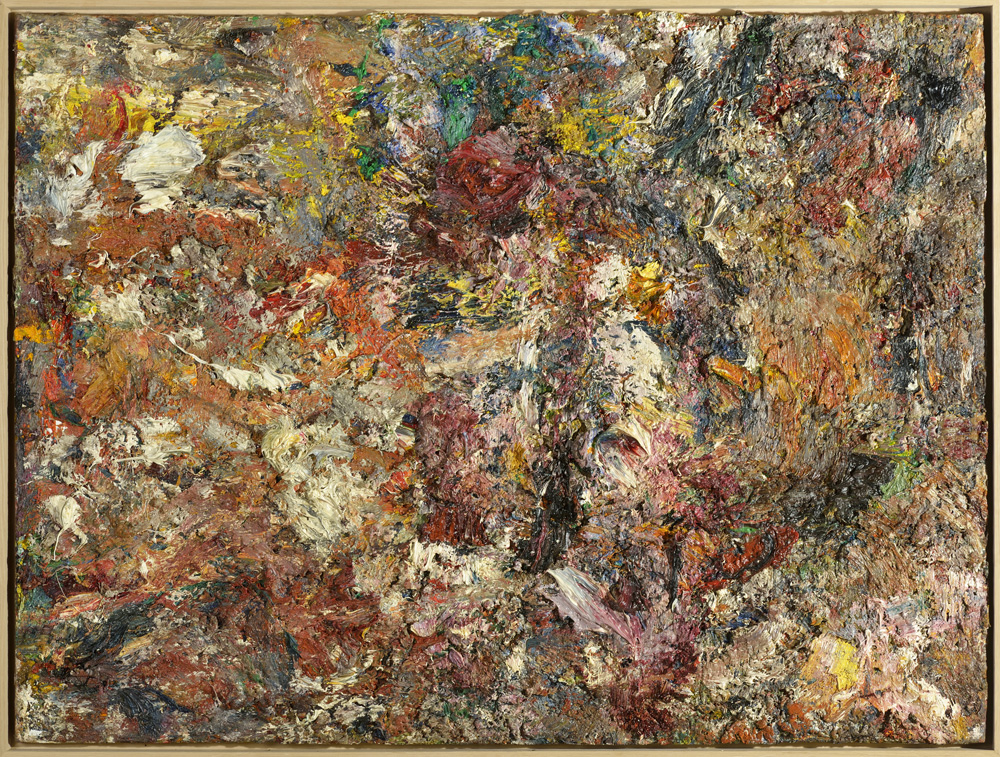

At the age of twenty-six he took his first trip, to nearby Holland. Here he became acquainted with Rembrandt and his work with colour and impasto. He also took longer trips, travelling to Spain and Italy in 1956. As abstract painting was celebrating its greatest triumphs, he was enchanted by Masaccio’s figurative frescoes. In Spain he sought the roots of expressive painting in the works of Goya, Velazqueze and El Greco. This is characteristic for Leroy. Although he lived through almost the entire 20th century (he was born in 1910 and died in 2000), his inspiring ventures into the past are reminiscent of Eighties postmodernism. The Dutch masters Van Gogh and Rembrandt have not been brought up by chance. To these artists one must add the tradition of Flemish expressionism, primarily represented by James Ensor, Constant Permeke and the entire school named after the town of Sint-Martens-Latem near Gent. Leroy spent his life living not far from the centre – from Paris; he lived in the centre of another region once called the Netherlands. The former Netherlands included the territory of what is now the Netherlands, the Kingdom of Belgium and the northern section of France along the border. At the time it was a part of Burgundy and supplied Europe with the best art that was being created. Names that stand out include the van Eyck brothers, followed by Peter Paul Rubens and later van Gogh and Rembrandt. One of the fathers of American abstract expressionism, Willem de Kooning, comes from the area. The roots of Leroy’s expressionism are evident and deliberate. Ideas of regional provincialism suddenly transform into an awareness of grand unity. It is as if the region still existed … and undoubtedly it does in the field of art. Leroy was a very perceptive artist who understandably did not close himself off in his own world untouched by other influences.

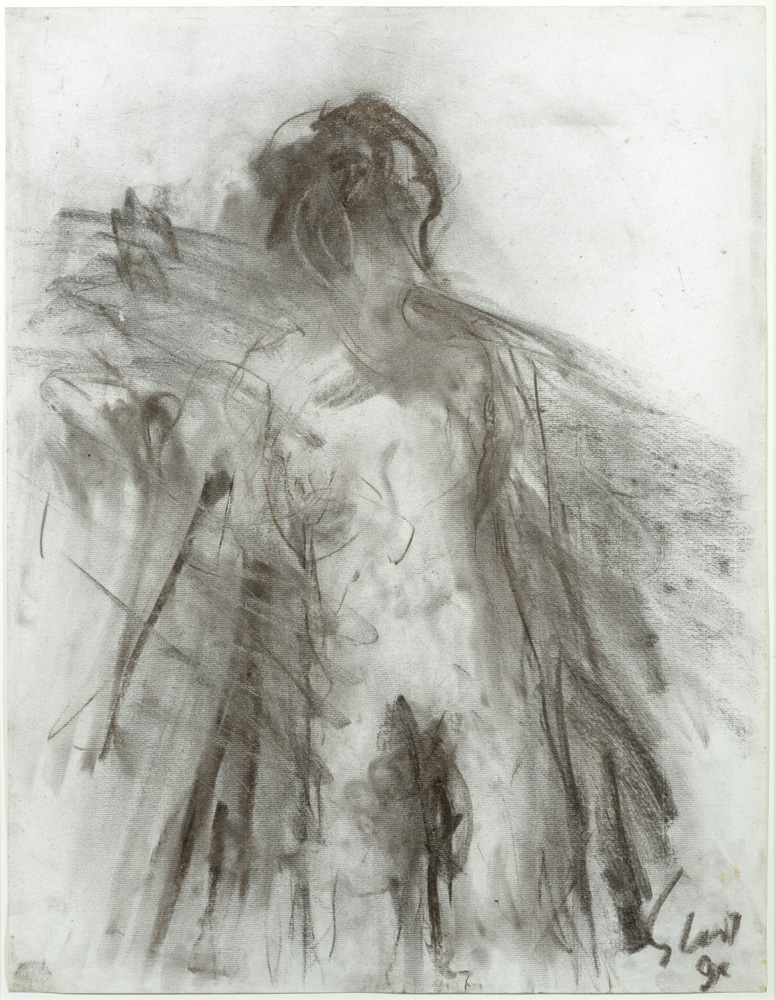

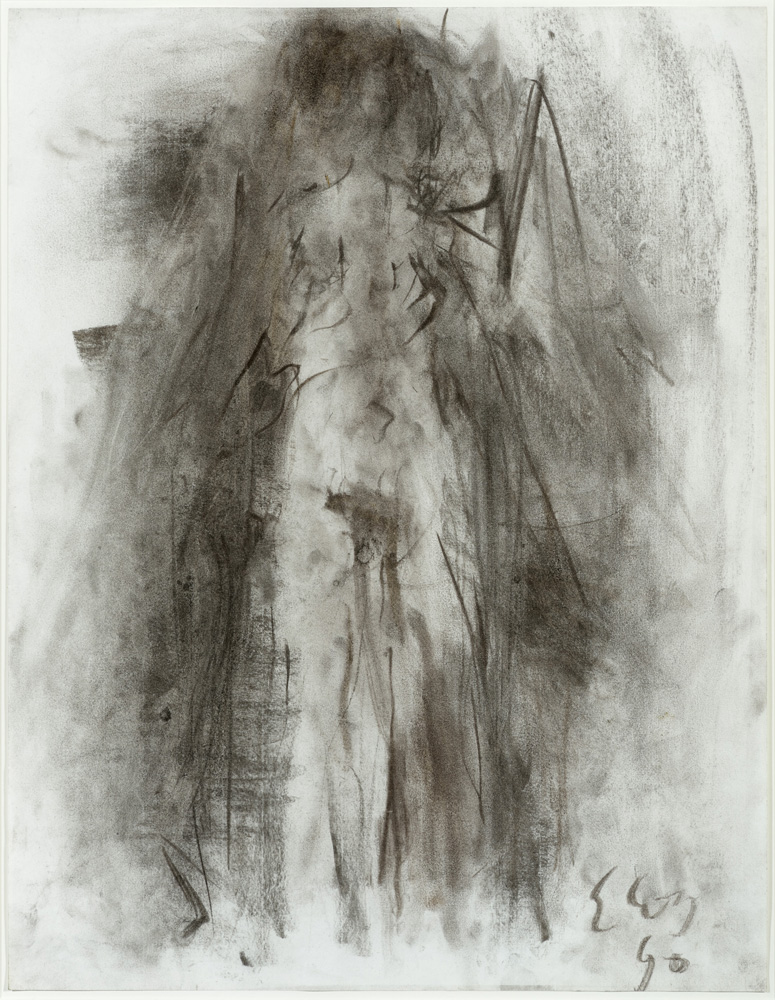

He was open to many stimuli, especially working with colours. His life’s motto could have been, “Colour is everything.” He could analyse the nuances of colour in works by old Dutch and Flemish landscape painters, which were so different from works by Italian masters. His delicately-fostered sense of colour was finally expressed in seemingly the opposite – Expressionism. It is still the same work with colour, contrasts and complementary colours, whether broken or direct. In Leroy’s case, traditional Flemish Expressionism was undervalued by German and Northern Expressionism. But in the Eighties, when Expressionism returned in a new form, primarily in Germany, Eugène Leroy’s art got the acclaim it deserved, though it is not associated much with the Neoexpressionist movement at the time and more with the work of Giacometti or Soutine. In any case, in the Eighties he received recognition from both critics and leading artists such as George Baselitz and Markus Lüpertz. It was no accident that at the same time, Jan Bauch and Josef Jíra received acclaim in Czechoslovakia. Interest in exhibits of Eugène Leroy’s work has also increased in Europe and the Americas since the Eighties, as can be testified in the number of exhibitions that have gone beyond the pale of his region. Leroy’s Expressionism is also based on the principles of Abstract Expressionism, pure abstraction and the movement known as Art Informel in the Czech Republic. Leroy’s colour is materialized, evidently becoming three-dimensional, and recalls the variable structure of the landscape created by the movement of the Earth’s crust. This universal landscape also includes human life. The layers of paint show human beings seemingly emerging from the dust, nudes merging and surfacing. As Leroy lived through almost the entire 20th century, he is sometimes called the painter of the century. As a member of his generation, he must have been influenced by interest in the lower currents of the unconscious and even more by the Existentialists, who found a very vibrant response in art from the late Forties through to the Sixties. Even art itself helped define and develop philosophical concepts. With the human nude, Leroy returns to the oldest, most classical motif in art and by shaping it into three-dimensional, multilayered structures, he expresses the basic question and main theme of visual art: “Who are we and where are we going?”

Mgr. Petr Štěpán – Art Historian